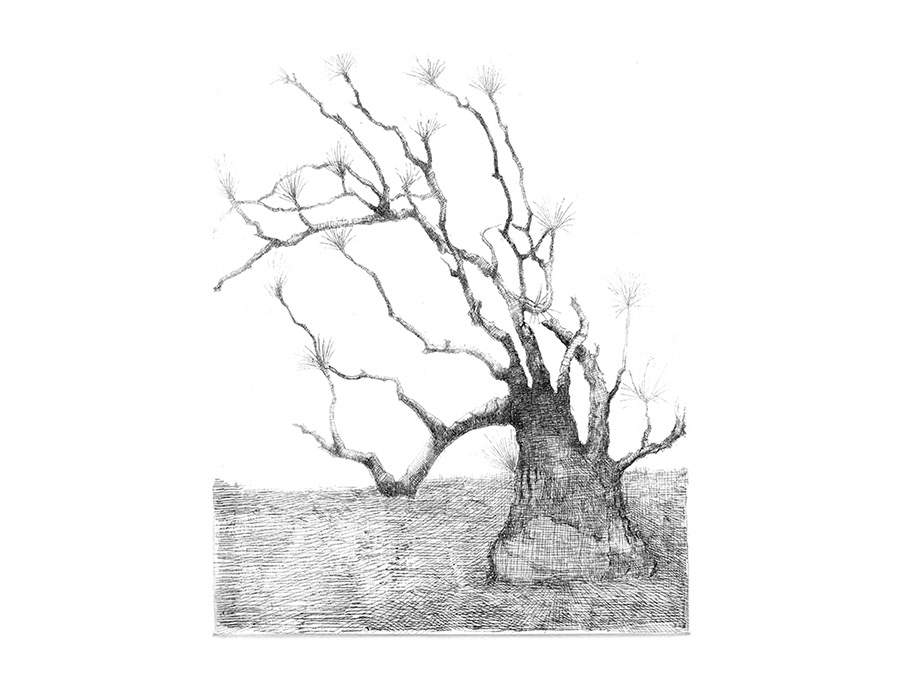

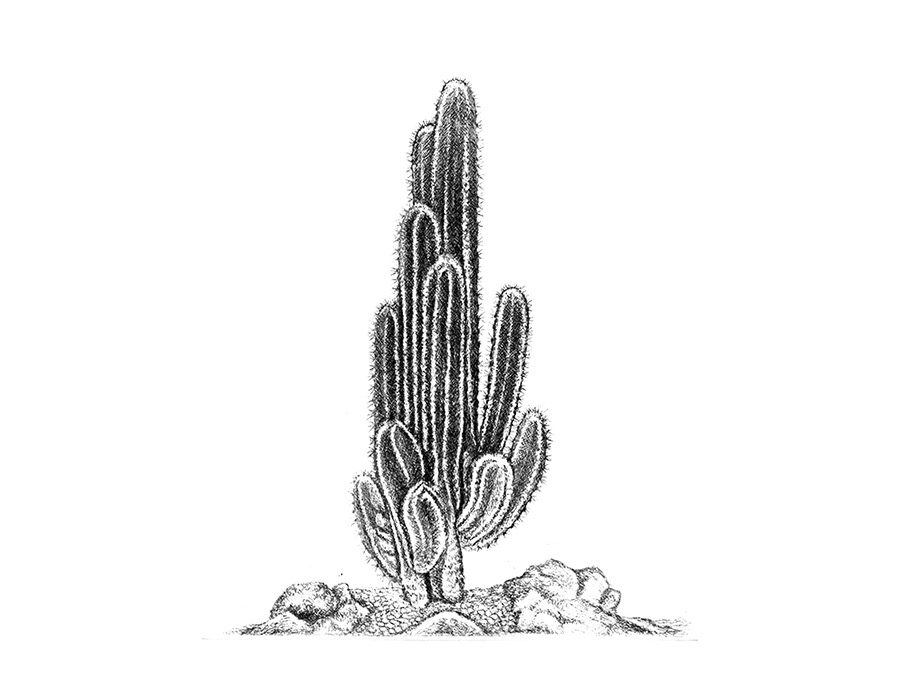

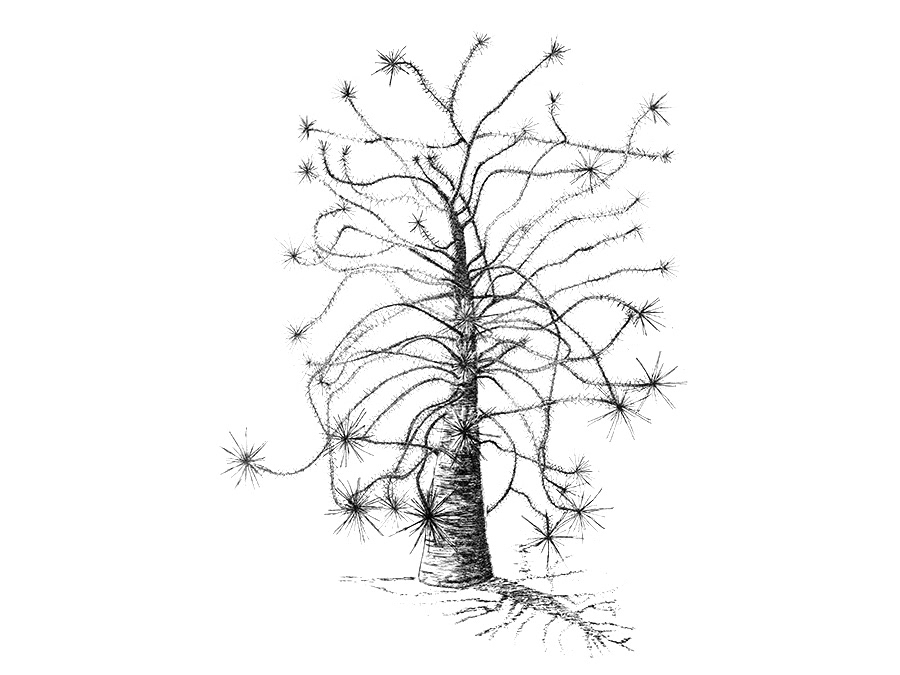

Pochote • Ceiba parvifolia

This tree that we planted next to the convent's old lime kilns was collected in the Cañada de Cuicatlán. Along with its sister species, Ceiba aesculifolia, and Ceiba pentandra, it forms one of the most important groups of plants in indigenous subsistence and cosmogony in tropical America: the succulent roots, tender fruits, and seeds are edible, the fiber is silky and disperses the seeds when the wind blows, it is used to fill pillows, and has been used in the industry as thermal insulation, and the wood is used both to make matches and to make canoes. Archaeologists have found abundant remains of Ceiba parvifolia in the caves of the Tehuacán Valley, where they provided food for collectors and hunters of the archaic period. The Ceiba genus belongs to the Bombacaceae family and comprises about 10 species endemic to America, plus an eleventh species that also grows in Africa. All of them are pollinated by bats, as are several tree elbows and magueyes. Frequently exceeding 60 meters in height, C. pentandra towers over the canopy in the humid tropical forests of America and Africa; C. parvifolia and C. aesculifolia, on the other hand, rarely exceed 5 meters in height, and are common in the dry tropical forests of this continent. All three species have a wide distribution in tropical Mexico, from southern Sonora to Chiapas and from Tamaulipas to the Yucatan Peninsula. Like other trees of the same genus, they are distinguished by strong thorns with a wide base and a sharp point that grow on the trunk. The pochote is the mother tree in Oaxaca. The Codex Vindobonensis narrates the birth of the ancestral couple that gives rise to the lords of the Mixteca; in a beautiful passage of the manuscript, the first aristocrat emerges from the split trunk of a ceiba tree. The Selden Codex provides more specific details: an umbilical cord connects the man with the tree, on whose bark appears an eye, a phonetic indication to specify that it is a pochote, yutnu nuu in Mixtec. The same scene is repeated in one of the bone tzotzopaztlis (machetes for weaving) found together with the gold jewels in Tomb 7 of Monte Albán, which seems to attest that the central figure buried there was a woman. The finely carved depiction leaves no doubt about the kind of tree being represented: thick thorns sprout from the bulky trunk. The ceiba madre is still alive in Oaxaca: the old women of Oítlan in Chinantla, and of Pinotepa on the Mixteca Coast, still narrate how the first people sprouted from its flowers. We thank Biologist Esteban Martínez Salas from the Institute of Biology at UNAM for identifying this species. Bibliography: Cruz Ortiz, Alejandra 1998. Yakua kuia. The knot of time. Myths and legends of the Mixtec oral tradition. CIESAS, Mexico, D.F. Jansen, Maarten 2002. Interpretation of the ceiba tree in the Selden Codex. Personal communication. Pennington, T. D., and J. Sarukhán 1998. Tropical Trees of Mexico; manual for the identification of the main species. Second edition. UNAM and Economic Culture Fund, Mexico, D.F. Smith, C. Earle 1967. Plant remains. In: Byers, Douglas S. (ed.) 1967. The prehistory of the Tehuacán Valley. Volume 1: Environment and subsistence. University of Texas Press, Austin.

You may also like