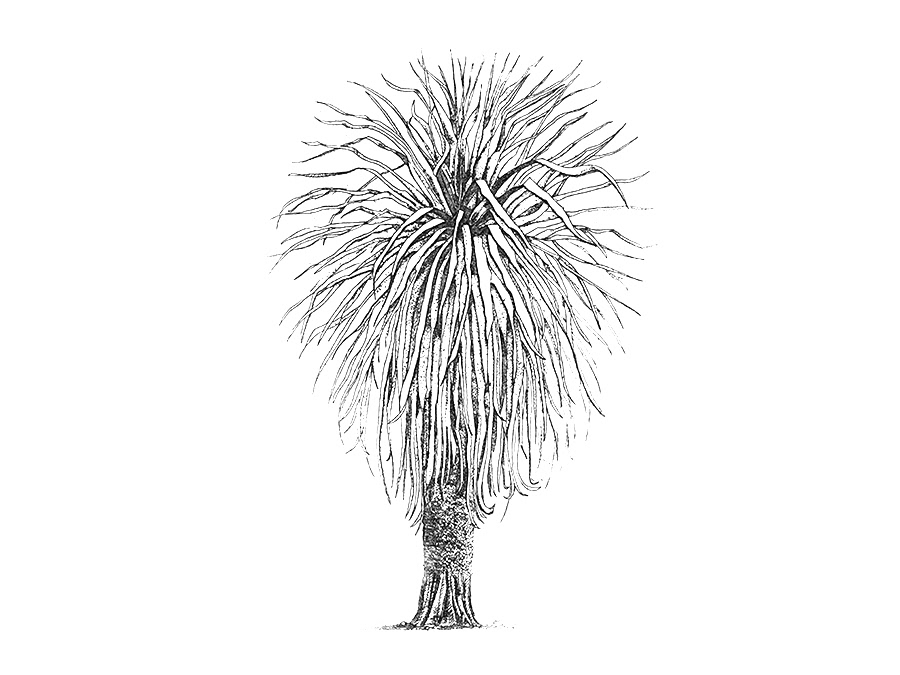

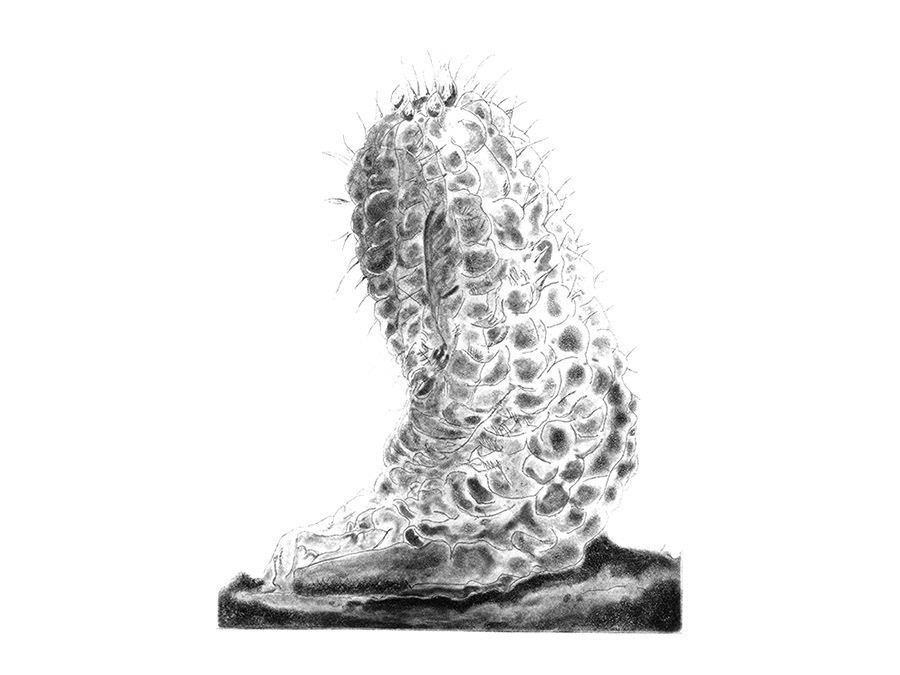

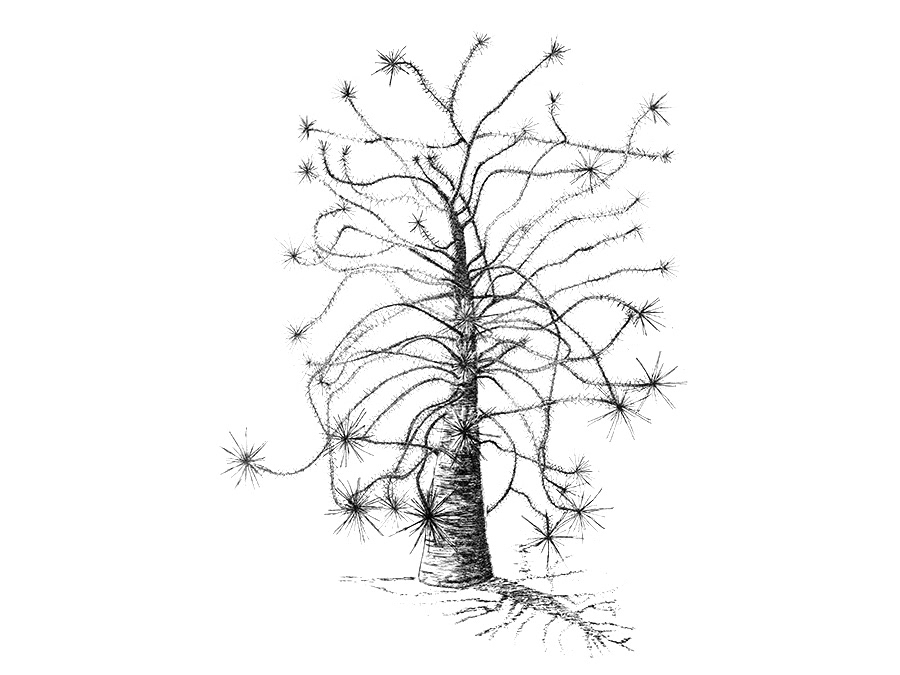

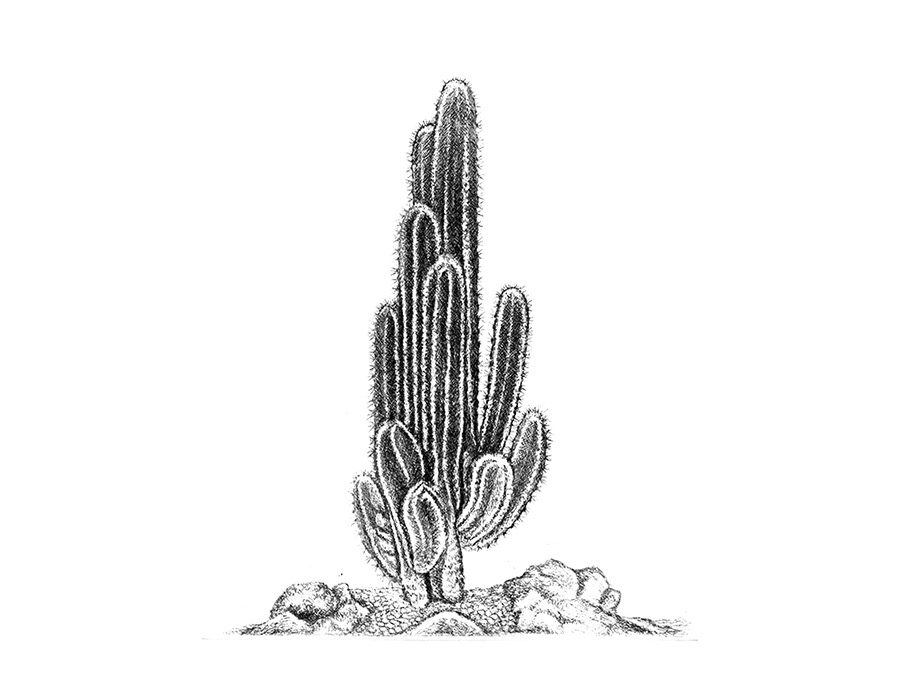

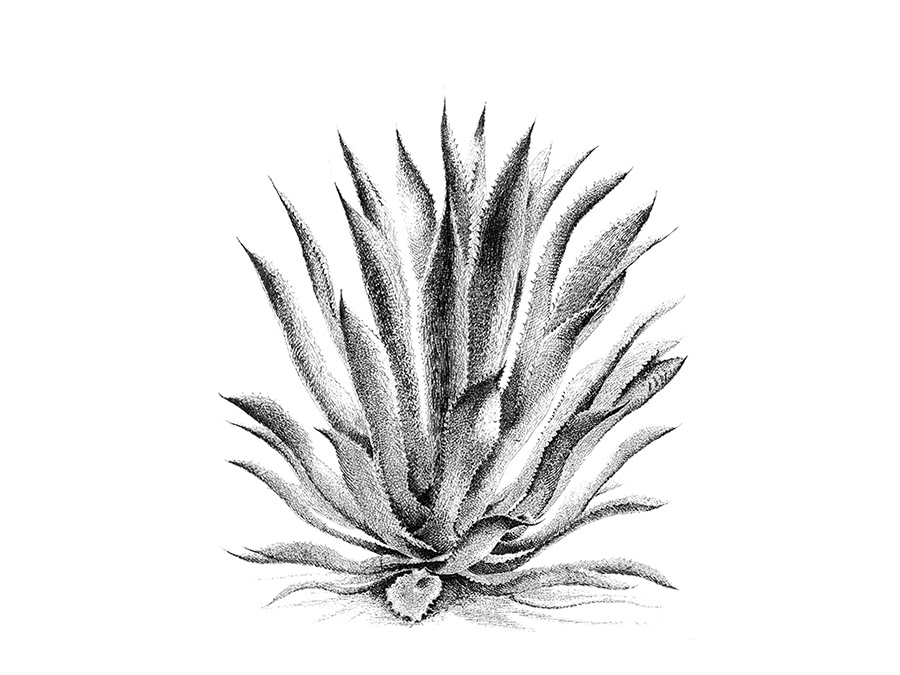

Deer Ear • Echeveria gibbiflora

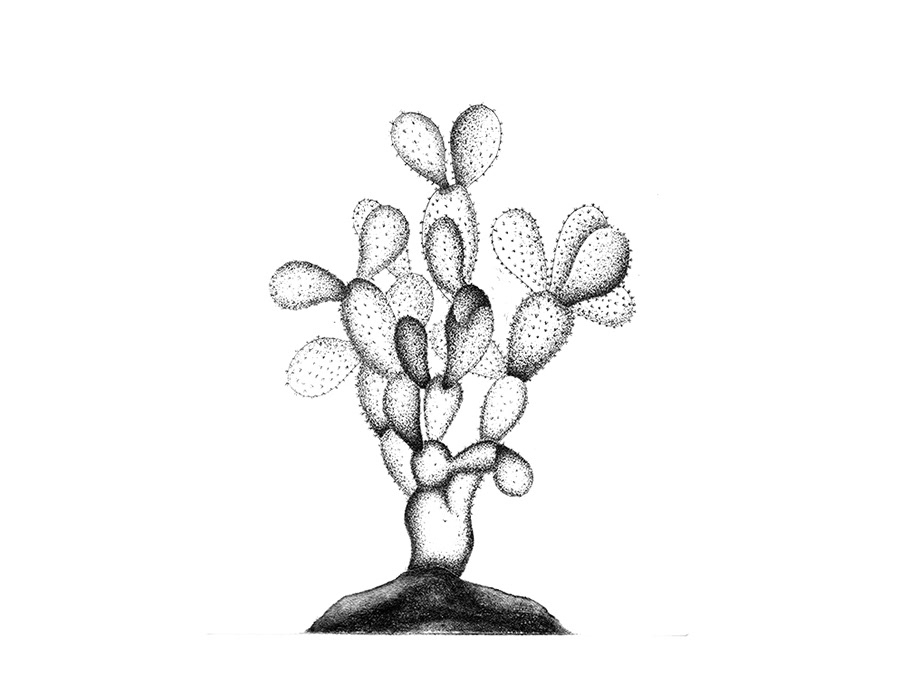

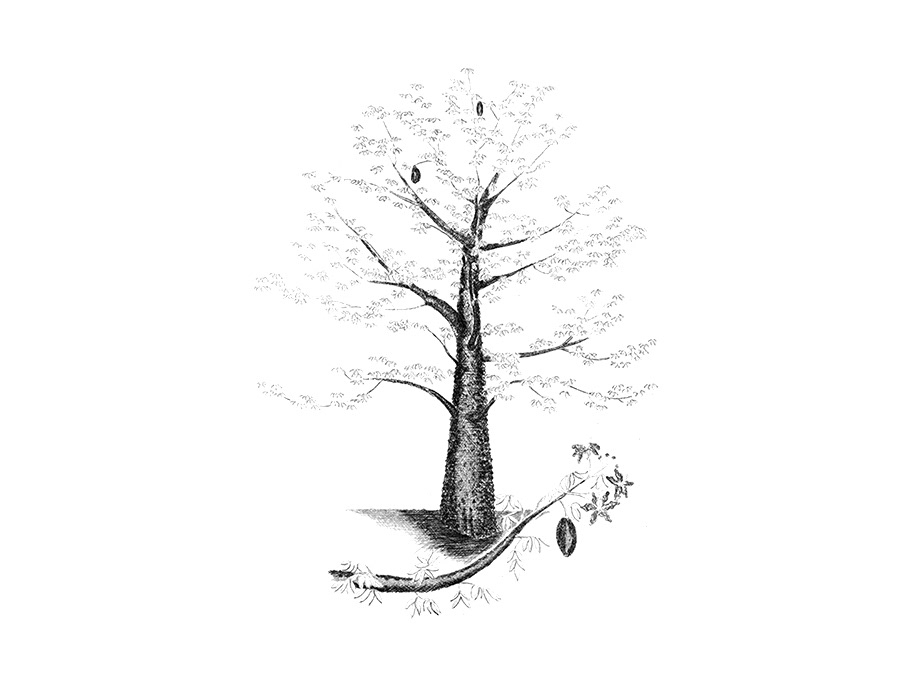

'Oreja de venado' is one of the common names for this plant in the countryside; in the city, it is called 'ombligo de reina', intolerably kitschy. The species has a wide distribution in Oaxaca and the Central region of the country and is often cultivated as an ornamental plant. The illustrated specimen comes from the hills near Mitla, where it grows in the wild. A robust Echeveria like this one is depicted as 'tememetla' in the Codex Badianus, a compendium of medicinal plants from the 16th century: it was used to treat mouth swelling. The 'oreja de venado' belongs to the Crassulaceae family, to which other Mexican species like 'siempreviva', 'cola de borrego', and others belong, traditionally cultivated in small pots to decorate walls and courtyards. The Crassulaceae are distributed worldwide, except for Australia and the islands of the western Pacific. The family includes more than 30 genera and around 1100 species. They are mostly succulent plants, which means that the leaves and stems have thickened as an adaptation to dry environments. Succulence involves reducing the surface-to-volume ratio, which decreases the transpiration rate, allowing the plant to retain more water. The genus Echeveria, with over 150 species, is restricted to the warm regions of this continent and has its center of distribution in our country. The flora of Oaxaca includes at least 17 endemic Echeverias, several of which are restricted to small areas in the Mixteca, the Cañada de Cuicatlán, and other regions. Over 30 crassulaceae exclusive to the State have been recorded, making it the region with the highest diversity and endemism of this family in the country. Every year, new Mexican crassulaceae are described, and it is likely that there are still undiscovered species in Oaxaca. The official list of threatened species, in the 1994 edition, marked Echeveria laui from Cañón de Tomellín as the only Oaxacan plant considered extinct. The wild population was decimated to such an extent that not a single plant remained in the site where it was originally reported. The motive behind the plunder was the greed of traders and collectors, who consider it one of the most beautiful and rare succulents. We thank Biologist Jerónimo Reyes Santiago from the UNAM Botanical Garden for identifying this species. Bibliography: • de la Cruz, Martín 1552 Libellus de medicinalibus indorum herbis. Latin translation by Juan Badiana. Spanish version with studies and comments by various authors, 1991. Fondo de Cultura Económica and IMSS, Mexico City. • García Mendoza, Abisaí, Pedro Tenorio Lezama, and Jerónimo Reyes Santiago 1994 Endemism in the Phanerogamic Flora of the Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca-Puebla, Mexico. Acta Botanica Mexicana, 27: 53-73. • Mabberley, D.J. 1997 The Plant Book: A Portable Dictionary of the Vascular Plants. Second edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.